Plants, like humans, can exhibit health problems for a variety of reasons, and as with humans, indicators often exist that can help diagnose the problem. By using a diagnostic-like process, you can determine the cause of the problem and make corrections in your growing practices to solve it as well as avoid future problems.

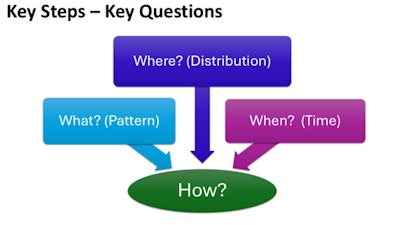

The three main questions of the diagnostic process are: what (pattern), where (distribution), and when (time/time frame) (Fig. 1). Approaching plant diagnostics with these basic questions in mind can help you focus your attention on efficiently saving your crop in a potentially high-stress moment.

Question 1: What? Fig. 1. The three main questions used to visually diagnose a problem are where, what, and when. All three must be utilized to make an informed diagnosis.Photo by Dr. Brian E. Whipker

Fig. 1. The three main questions used to visually diagnose a problem are where, what, and when. All three must be utilized to make an informed diagnosis.Photo by Dr. Brian E. Whipker

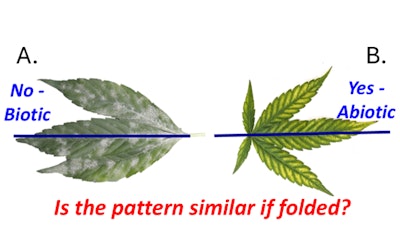

When determining if the problem is the result of biotic (pathogen or insect) or abiotic (nutritional or physiological) origin, a key step is looking for symptoms on the foliage—what is the pattern on the plant?

If you were to take a leaf exhibiting symptoms and draw a line down the center (see Fig. 2), are the symptoms symmetrical? If the leaf symptoms are not symmetrical, in most cases this points you in the direction of biotic problems such as pathogens or insect damage (see Fig. 2(A.)). If the symptoms appear symmetrically on the leaf, this is a strong indication that you are experiencing an abiotic problem such as nutritional deficiency or physiological cause (see Fig. 2(B.)).

This simple test is best performed on leaves that have symptoms covering ~33% of their surface. Otherwise, critical early health issue evidence could be lost. For example, the pattern difference is noticeable at the initial infection of powdery mildew, but the disease will eventually spread and cover the entire leaf surface, thus negating this diagnostic check. This is another reason to have a good and consistent scouting program to catch problems early. Fig. 2: When determining the pattern on a leaf, imagining a line down the center of the leaflet and determining if it is symmetrical is a helpful tool in determining if the problem is biotic (nonsymmetrical, such as with powdery mildew as seen on the A side) or abiotic (symmetrical, as with magnesium deficiency on the B side).Photo by Dr. Brian E. Whipker

Fig. 2: When determining the pattern on a leaf, imagining a line down the center of the leaflet and determining if it is symmetrical is a helpful tool in determining if the problem is biotic (nonsymmetrical, such as with powdery mildew as seen on the A side) or abiotic (symmetrical, as with magnesium deficiency on the B side).Photo by Dr. Brian E. Whipker

Question 2: Where?

The next step is looking at symptom distribution—where in the greenhouse or on the plant are the problems occurring?

If the distribution of impacted plants is non-uniform, such as scattered plants or pockets throughout the growing space, you can start to suspect biotic problems (see Fig. 3). For example, during mite infestations, a small number of plants typically will be initially infested before spreading to surrounding plants. Another biotic example is Pythium root rot, which will tend to start with a single plant amongst many healthy ones.

In contrast, if the problem is evenly distributed and/or uniform throughout the entire growing space or at one end of the greenhouse compared to the other, you would start to suspect abiotic problems (see Fig. 4). For example, if an entire greenhouse bench is exhibiting similar symptoms, the irrigation equipment should be checked for proper function. Fig. 3: When single plants or clustered plants are exhibiting problems, this points to biotic problems occurring such as Pythium root rot (shown here) or insects.Photo by Dr. Brian E. Whipker

Fig. 3: When single plants or clustered plants are exhibiting problems, this points to biotic problems occurring such as Pythium root rot (shown here) or insects.Photo by Dr. Brian E. Whipker

Additionally, consider where on the plant the problem is occurring: Is it on the roots, stem, upper or lower foliage, or on the floral structure? Breaking a plant down into parts will clue you into what the potential problem could be. For example, many micronutrient deficiencies appear in the younger foliage, while macronutrient deficiencies of nitrogen, phosphorus, potassium and magnesium generally occur in the lower foliage.

Question 3: When?

Onset and duration–when and or how long did it take visual symptoms to manifest are important questions to answer since they can eliminate many problems that exhibit similar symptoms.

When symptoms appear quickly—within 24 to 72 hours—you can suspect abiotic problems such as chemical phytotoxicity (see Fig. 5), environmental stress, or nutrient toxicity. If symptoms appear gradually—over one to four weeks—the potential list of culprits is much larger and includes diseases, insect damage (Fig. 6) or nutritional deficiencies. Fig. 4: If an entire greenhouse or flat is exhibiting similar problems, this points to abiotic disorders such as low fertility (shown above), or physiological problems.Photo by Dr. Brian E. Whipker

Fig. 4: If an entire greenhouse or flat is exhibiting similar problems, this points to abiotic disorders such as low fertility (shown above), or physiological problems.Photo by Dr. Brian E. Whipker

Evaluating

Utilizing these three questions can help narrow down the potential cause(s) of the problems that you are observing in your crop (see Fig. 1). Fig. 5: Rapid development of visual symptoms (within 48-72 hours) directs your attention to abiotic problems such as chemical phytotoxicity (shown above), or water stress.Photo by Dr. Brian E. Whipker

Fig. 5: Rapid development of visual symptoms (within 48-72 hours) directs your attention to abiotic problems such as chemical phytotoxicity (shown above), or water stress.Photo by Dr. Brian E. Whipker

While this is an excellent starting point for narrowing down the possibilities, oftentimes problems can occur in combination and can make diagnostics tougher, such as nutrient-stressed plants being more susceptible to disease, or root rot leading to iron deficiencies.

Understanding the causes of the problems is an important step to preventing problems in future growing seasons. Additionally, learning the top problems that you regularly encounter will help you make informed decisions for prevention or early diagnosis and treatment.  Fig. 6: When visual symptoms take longer to manifest or intensify over time, you can start to shift your attention to insect damage (above), pathogens, or nutrient deficiencies.Photo by Dr. Brian E. Whipker

Fig. 6: When visual symptoms take longer to manifest or intensify over time, you can start to shift your attention to insect damage (above), pathogens, or nutrient deficiencies.Photo by Dr. Brian E. Whipker

Patrick Veazie, Paul Cockson, and Brian E. Whipker are researchers with North Carolina State University in Raleigh, N.C. Whipker is also a professor and commercial floriculture extension and research specialist.