David Paul Watson, known in the cannabis community as “Sam the Skunkman” for his breeding expertise, including developing world-renowned cultivar Skunk #1, died on Jan. 27.

Watson and his wife of 54 years, Diana, were en route to spending a month with friend Todd McCormick, a longtime cannabis activist and fellow breeder who announced the death Tuesday morning on social media.

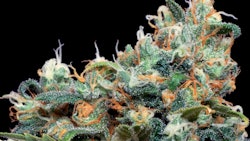

“His passion for cannabis and contributions to the cannabis community are legendary,” McCormick wrote. “He was my friend, my teacher and one of the nicest people I’ve ever met in my life. Please light one up and smoke one for the Skunkman because some of his work is most likely in the cannabis you’re burning today.”

Watson departed this world as a husband, as a father of two daughters, and as a grandfather.

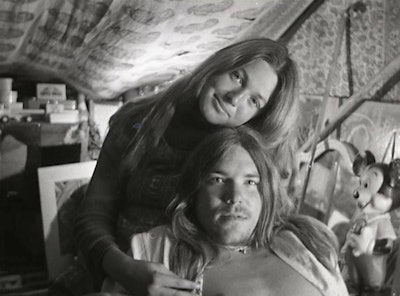

David Watson and Diana Watson in the 1960s.Photo courtesy of Ryan Lee/Watson Family

David Watson and Diana Watson in the 1960s.Photo courtesy of Ryan Lee/Watson Family

He was also the patriarch of the entire cannabis industry, fellow breeder Ryan Lee, of Chimera Genetics, told Cannabis Business Times. Lee spent Tuesday with Diana helping to make family arrangements in the wake of Watson’s death.

“I called David the cannabis silverback because he was kind of the big gorilla in the whole pack, and I don’t think he meant it in an aggressive way, but he always liked to make it known that he had been there and done it first,” Lee said. “And, in reality, he had always been there and done it first. People are still doing things and replicating work that he did 20 years ago—triploids and polyploid cannabis, and all this kind of stuff. So, he really was the founding father of the industry, of the entire industry, both the seed industry and the medical industry.”

Watson’s knowledge and passion for the cannabis plant—wanting to know everything and everyone associated with its advancement—placed him as a central atom of the present-day cannabis story, Lee said.

Through this unmatched thirst, Watson became a mentor to many and a friend to even more. The news of his death has been met with condolences from throughout the industry.

“He was larger than life,” Marcus “Bubbleman” Richardson, who’s known Watson for more than 25 years, said Tuesday on social media.

“I will never forget the email he sent me to introduce himself to me,” Richardson wrote. “I knew immediately who it was, and I was blown away he was contacting me. Little did I know that we would develop a friendship and mutual respect for one another. He was truly a father figure to me, and I will never forget him. Now my thoughts are with Diana, his wife and best friend for over 50 years. … I loved you brother and will never ever forget you.”

Richardson added: “You made me a better hash maker of that there is no doubt. I will carry the lessons and learnings you shared with me for the rest of my life. And I will look forward to the day where I see you again to smash endless dabs out of a phat Roor Bong. Bless up Sam, we LOVE YOU.”

An American cannabis breeder, Watson is also credited for developing Haze, among other popular cultivars.

In addition, Watson is known for contributing to horticultural research on pests and plant diseases alongside Robert C. Clarke, a writer, photographer, ethnobotanist, plant breeder and textile collector. Watson co-wrote, along with Clarke and John McPartland, the book "Hemp Disease and Pests."

RELATED: David Paul Watson (aka 'Sam the Skunkman') – Obituary by Robert C. Clarke

Watson and Clarke began working together in the 1970s, and each contributed published work on cannabis cultivation and breeding that helped lay a foundation of expertise for the cannabis community.

In 1979, Blotter magazine published an article Watson wrote under the pen name “Selgnij” (jingles spelled backward) that was titled “Sun, Soil, Seeds and Soul: … just part of what it takes to grow righteous, potent, sticky California cannabis.”

Jingles was another alias for Watson, with the genesis for that nickname going back to the 1960s, Lee said.

“David was quite a hippied-out dude in the late sixties and seventies, and he used to wear, he had these little bells on his shoes or pants, and so everywhere he walked, he jingled,” Lee said. “And that actually became his name; his hippie name was ‘Jingles.’”

In the article from 1979, Watson discussed growing cultivars adaptive to California’s climate as well as those with traits associated with geographic regions from around the world. Also, he provided key knowledge of best cultivation practices and detailed breeding techniques in the article.

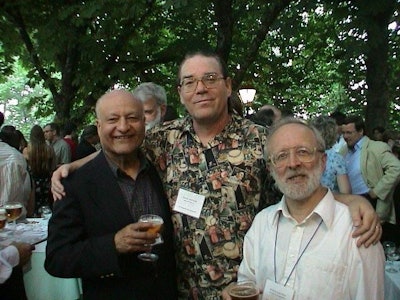

From Left to Right: Israeli chemist Raphael Mechoulam (credited for elucidating the structure of THC and the endocannabinoid system), breeder David Watson and U.K. researcher Roger Pertwee.Photo courtesy of Ryan Lee

From Left to Right: Israeli chemist Raphael Mechoulam (credited for elucidating the structure of THC and the endocannabinoid system), breeder David Watson and U.K. researcher Roger Pertwee.Photo courtesy of Ryan Lee

In the 1970s and early 1980s, Watson and Clarke ran breeding projects in the U.S., meeting with fellow horticultural authorities Mel Frank and Ed Rosenthal, while yielding seeds and breeding parents that were selected to make lines that are around today, according to Beard Bros Media.

Specifically, Watson’s work is connected to one of the earliest cannabis seed companies to gain notoriety in the U.S.: Sacred Seed Collective. This company was “instrumental in developing the early [cannabis hybrids] that helped transform American ‘homegrown’ cannabis from a ditchweed laughingstock to the envy of the world,” according to High Desert Relief.

In those early breeding years, Watson was among a group of emissaries in California’s counterculture who often traveled the world looking for unique landraces of cannabis, according to The New York Times.

“The most influential of these collectors was a man named David Watson,” the Times reported in 2020. “In the early 70s, Mr. Watson sold his possessions and began hitchhiking from Morocco to India, befriending local pot growers along the way.”

Skunk #1, the cultivar which Watson shares his alias with after being involved in its prototype, is a hybrid of Afghan (indica), Mexican (sativa) and Columbian Gold (sativa), according to Leafly. Skunk #1 won the inaugural High Times Cannabis Cup in 1988.

In 1985, Watson left Santa Cruz, Calif., according to VICE, and moved to Amsterdam a month later with a box claimed to have some 250,000 seeds. In 1986, he began Cultivator's Choice, Amsterdam’s first cannabis seed company.

Haze and Skunk weren’t the only lineages Watson took overseas to breed and develop, Mojave Richmond, a developer of many award-winning varieties, told Cannabis Business Times.

Watson brought Skunk #1, Haze, California Orange, Early Girl and Afghan #1 and Durban Poison, which both came from Mel Frank, Richmond confirmed. Those varieties invigorated the Dutch cannabis scene with an infinite number of hybrids resulting in the following years.

After meeting with emissaries in Amsterdam, Skunk #1 became a staple in seed banks throughout the Netherlands’ capital, as the Dutch remained at the forefront of the global cannabis scene throughout the 1990s.

Watson went on to found HortaPharm B.V., a medical cannabis corporation, in 1992 in Amsterdam, working with Clarke to create a genetic library with seeds from around the globe to breed hybrids with desirable traits, according to High Desert Relief. The company was licensed by the Dutch Ministry of Health for three years to conduct scientific research on cannabis.

Watson had the ability to navigate the legal system and obtain licenses in a foreign country where the nationals of that country weren’t able to jump through those same hoops, which created jealousy in Holland, Lee said.

“So, there was a lot of resentment and distrust about David, which you’ll be able to find online in the form of people thinking that he was a DEA or a CIA agent,” Lee said. “There was all this silly stuff that was said about him, of course, none of which was true. But they created this alternate persona for David that was based on this idea that he was an informant and all this nonsensical stuff that has no basis in reality. And the funny part was that they just misunderstood.”

At HortaPharm, Watson established a research team, led by Dr. Etienne de Meijer, which was the first to use silver thiosulfate as a breeding method to “self” cannabis plants and create single cannabinoid cultivars, according to Vancouver-based Segra International Corp., which Watson joined as an advisory board member in 2018.

Breeder David Watson and GW Pharmaceutical founder Dr. Geoffrey Guy.Photo courtesy of Ryan Lee

Breeder David Watson and GW Pharmaceutical founder Dr. Geoffrey Guy.Photo courtesy of Ryan Lee

Through a licensing agreement, HortaPharm provided its genetics to GW Pharma, along with organic cultivation and integrated pest management expertise. Through this partnership, GW Pharma produced two cannabinoid-based pharmaceutical medicines approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration: Sativex and Epidiolex.

Sativex is a mouth spray used to treat muscle stiffness and other symptoms associated with multiple sclerosis, while Epidiolex is used to treat seizures from rare forms of epilepsy in young children, including Lennox-Gastaut syndrome and Dravet syndrome.

“HortaPharm leads the world in its understanding of cannabis botany and has built up over many years the most extensive ‘living library’ of medicinal cannabis varieties,” Watson said in July 1988. “As soon as Dr. Guy’s clinical research indicates the exact desired composition, our scientists can breed and register new medicinal varieties.”

Watson and Clarke also founded the International Hemp Association in 1993, which published a scholarly journal dedicated to hemp agronomy research.

The founding of that association further exemplified how far ahead of his time Watson was, Lee said.

“The founding premise of the International Hemp Association was the dissemination of information regarding cannabis in all forms—medicinal, industrial, and recreational,” Lee said. “It wasn’t just pre-states legalizing; it was pre-countries all over the world even accepting hemp. Forget drug cannabis; back then even growing hemp in most of the world was restricted. The purpose of the International Hemp Association was to share information about the cannabis plant in general.”

Before various countries legalized the commercial production of hemp—such as Canada did in 1998—government researchers contacted the International Hemp Association, Lee said. Watson, who had a catalog of dozens of hemp varieties, would send the researchers large samples of each variety to allow them to have a diverse collection of hemp germplasm to start their trials to see which varieties might work best in their region, Lee said.

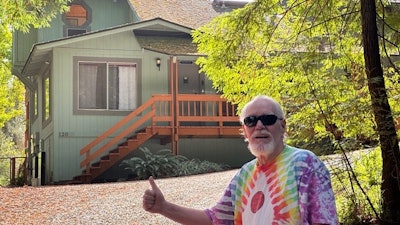

David Watson, aka "Sam the Skunkman"Photo courtesy of Todd McCormick

David Watson, aka "Sam the Skunkman"Photo courtesy of Todd McCormick

One of Watson’s notable attributes was that he was always willing to share information freely, and he always had his “finger on the button” when it came to the most up-to-date research in the community, Lee said.

“He was a beautiful man, incredibly intelligent and singularly focused on cannabis,” Lee said. “If you were interested in cannabis and forwarding the plant and doing work with the plant, and especially if you had the finest quality of hashish, he’d be interested in being your friend and speaking to you. If you didn’t have anything to do with cannabis and weren’t interested in cannabis, he wanted literally nothing to do with you.”

Family arrangements to pay tribute to Watson’s life were still being finalized as of Wednesday morning.

However, Lee said one of Watson’s wishes was to have his ashes shared with his friends and that those friends use the ashes in their next cannabis crop. Half of his ashes will stay in California, while the other half will go back to Europe to be distributed.

“To me, David is cannabis,” Lee said. “In that act of his ashes, he is going to become cannabis.”

This is a developing story. More details will be updated this week.